COVID, week 1 & Kelly McDonigal, PhD’s The Joy of Movement

At the rate we’re going, I’ll have little memory of this all in a week, so I suppose it’s worthwhile to write it out here as much for you — to compare to what’s going on where you live — as it is for me, to remember how fast life can change.

COVID-19 seems to have had a similar effect on time as does child-rearing, wherein the days are somehow really long and really short at the same time. It sounds impossible until you’re in the thick of it, and then suddenly, you get it.

Since last week’s writings — which seem like a lifetime ago at this point — Santa Clara County is one of many counties in northern California to have issued a Shelter in Place, basically barring residents from leaving home except for very specific reasons, like going to a job that’s essential for society or for getting groceries or medicine. Fortunately, leaving home to exercise outside is allowed, though stipulations still apply: maintain the social distance of at least six feet (unless you’re with people with whom you reside), no big groups (nothing over 10, if I recall correctly), and so on.

It’s a little weird, to say the least.

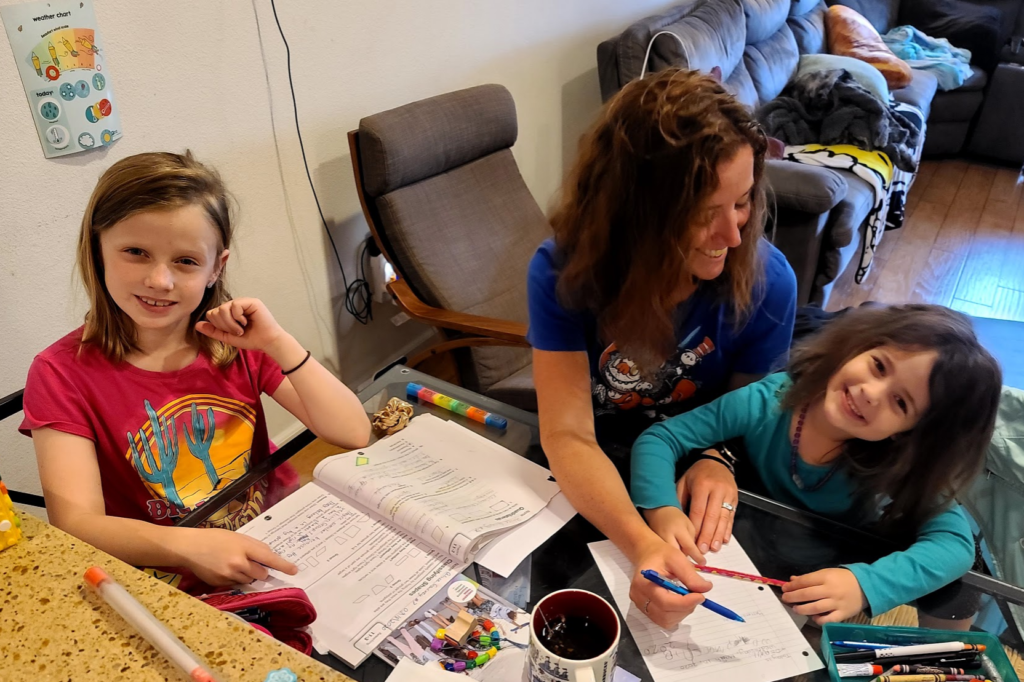

In the mix of our homeschooling adventure — oh, right! I forgot to mention that A’s school is closed at least through the beginning of April and G’s preschool is right there as well, though it’s quite likely that both children will be out of school for (much) longer. It was around mid-day on Friday, March 13, that schools in SCC began communicating with families that they were closing for several weeks to help mitigate the virus’s spread. Somewhere around that time, late last week, most/a lot of the tech companies here (or whose hdq are here) told their entire workforces to transition to working remotely, and so it seemed nearly overnight, we (my family yes, but California in general) went from a fairly typical go to school, go to work, go to extracurriculars, do life as you know it routine to a screeching, full-stop halt, a life where if whatever it is isn’t happening out of your home, chances are quite, quite high that it ain’t happening at all… or if it is, it’s in a way unlike anything you’ve ever done before.

Again: it’s all a little weird, to say the least.

The kids and I have been diligent about getting outside for fresh air (PE? sure!) because that’s a normal thing to do, even if what we’re doing right now — having school at the kitchen table, led by yours truly– is completely abnormal. (Quick tangent here to say that my mom is a retired public school educator and education administrator, so I’ve grown up knowing first-hand how overworked and underappreciated these souls are. Props, again, to the educators who make the world go round. I spent more time this morning explaining, and re-explaining, to my preschooler the various ways one could make a capital- and lower-cased X than is probably necessary. I know I’m no substitution for Ms. M, but deargod!). Anyway.

We have been following a daily schedule to the best of our abilities because I’m pretty sure most of us (humans in general, yes, but my progeny in particular) do better with routines than they do with chaos — and especially during a trying time like now, with a seeming million unknowns flying around and news (fake or otherwise) coming at us at light speed. My job is to give them normalcy, so even in the utter lack thereof wherein we’re currently residing in Silicon Valley, I am trying to make our days have rhythms and cadence similar to what they’d have at school.

Trying, of course, is the operative word.

In recent weeks, I’ve mentioned how good The Joy of Movement was, and I still wholeheartedly stand by it. My quick and dirty book review of it is basically that if you’ve ever considered yourself someone who loves to move your body — however you do it — because it just makes you feel good, this book is for you. It backs-up all of those hunches you’ve had about exercise’s effect on you, particularly on your mental health, with all types of research and studies that are meaningful and pertinent.

If the opposite is true — that you’ve never really considered yourself to be someone who quote-unquote LIKES exercise — this book is still for you. I think the author does a solid job of convincing everyone that they have something, a few things, really, to gain from exercising, in terms of their mental health. It’s a solid read, fairly quick, and if you’re in the market for something from which you want to walk away feeling inspired (and chompin’ for a run [or your movement of choice]), The Joy of Movement is for you.

Finishing The Joy of Movement right before COVID-19 blew up reminded me of how important I deem exercise (and specifically, running) to my health. It’s as natural to me each day as, I don’t know, breathing. Ninety-nine percent of the time, my movement of choice brings me immense joy, regardless of my pace, my distance, how much climbing I did, or any other metric that only runners care about, and I’ve often ruminated on how lucky I am to be able to do it in the first place. I’m fortunate to be able to want to do it and be physically able to, yes, but I’m also fortunate to be in a position where my life circumstances allow me to. My privilege isn’t lost on me. (Another quick aside to say that Nick Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn’s new book, Tightrope, is so, so good and also heartbreaking. Reading it in the midst of the COVID shutdown is another level. More to come, highly recommended).

Regarding running and COVID: over the past few days, with COVID and shelter-in-place and everything else engulfing everyone’s attention span, I noticed that my running has changed ever-so-slightly. It’s not necessarily because my goal races are out the window, which they absolutely should be — Big Sur announced its postponement last week, the spring PA schedule is decimated, and I imagine Mountains to Beach will make their postponement announcement any day now — but I think it’s because I’ve instinctively needed running to be something other than it was for me in days prior.

In the past week, all I want is to hear the birds singing, or the cows bellowing, or nothing at all.

Hearing my breathing is enough.

Seeing the electric pink of a burgeoning sunrise reminds me that I’m here for this, right now.

I could tell you what yesterday was like, or I could take a stab at hypothesizing what tomorrow will bring, but in doing either (or both), I’d be missing out on what’s unfolding before me, all the messy and uncomfortable bits of it.

Or I could just stay right here, in this present moment, and roll. It might be a colossal failure, and it might not be pretty, but trying again and again is the only option.

If movement has taught me nothing else, it has taught me the value in staying put — uncomfortable as it may be sometimes — and that eventually, a path appears, and the only way out is through.