I had a stroke

Jesus, how ’bout that title!?

February 4th was the first PA race of the 2018 circuit, a new-to-the-series race up in Sacramento that was Super Bowl-themed, the Super Sunday 10k. I had been looking forward to racing that tough distance — my first race since CIM in December — and after taking a decent amount of R&R in December and getting back to a 200+ mile month in January, I felt ready to go, excited to blow dust off my racing legs, and just go do what I absolutely love to do, alongside my teammates. Lisa began coaching me again in January, and we both felt that things seemed to be moving in the right direction and that my 2018 racing would begin positively.

————–

Sunday – Day Zero

In Sac, when I exited my van (after driving uneventfully for about 2 hours), I remarked to my teammates Hannah and Claire, “wow, my head hurts.” There was nothing dramatic to my statement; I just noticed right away that my head hurt, and I thought it was odd. I rarely have headaches — maybe a few each year — and have no history with migraines. Yet while my head hurt, it wasn’t debilitating. Ask any runner, and she’ll likely tell you that sometimes going for a run — even (especially) something slow and casual — can make you feel better when you’re not feeling great in the first place. You may be feeling sub-par for any number of reasons — because you’re tired, sore, hungry, have a headache, in need of caffeine, whatever — but it’s something about the cathartic nature of running, an activity that can get the blood flowing, so to speak, that often makes most of us feel better afterward. This notion isn’t unusual.

Granted, I thought it was shitty I got this headache right out of the blue, and literally like 20 minutes before the start of my race, but I began my team’s warm-up, casually scooting along at about 8:40 minute miles (more than 2 minutes/mile slower than what I was preparing to race), and figured that by the end of the warm-up, my head would feel better. Absolutely nothing was exceptional about the warm-up: nothing. We were chatting along, running casually; it was perfect running weather (probably in the high 40s); and we were moseying along on pancake-flat pavement, not straining or exerting ourselves or anything. It was one of those total vanilla runs — as a lot of runs are — and nothing to write home about. My head just hurt, and it was annoying. What shittyass timing to have a bad headache, I thought.

Going for an easy 2 miler didn’t ameliorate things, much to my chagrin. Instead, the headache worsened: and significantly. My annoying headache had jumped from the low end of the pain scale to basically a million+, and I was convinced that someone had come up from behind and just jacked me in the head with a hammer because the pain was so acute, so intense, and so localized. Why would my head be throbbing like this? I felt super nauseated and dizzy and wished that I could gag myself to induce vomiting because I was certain that if I threw up, I’d feel better.

My throbbing head made me feel like absolute hell, and even after scoring an ibuprofen from my teammates, I frustratingly told them that I couldn’t race because I suddenly felt so, so sick. The dizziness, fatigue, nausea, and headache all but sealed my assumption that I had just been violently beset with the horrible flu that everyone had been talking about.

The pain was high in my head, right under where my high ponytail would be, and naively, I thought that maybe my too-tight or too-high ponytail, what with my super long and super thick hair, was hurting me. This idea sounds silly on paper, but if you have long or thick hair, you know exactly what I’m talking about. Even after taking down my hair, though, the pain persisted.

Honestly, I have never been so incapacitated — and so quickly — before in my entire life.

I have never experienced such awful and completely debilitating pain.

Maybe a better way to describe the pain is to compare it to childbirth, since that’s something that a lot of people can understand. I’ve had two unmedicated, intervention-less childbirths, and honestly, the pain with those didn’t hold a candle to this headache. With childbirth, for one, you have a pre-existing condition (being pregnant), so while that doesn’t prepare you, per se, for the actual pain of delivery and labor, you can at least mentally prepare for the act, to a degree, because you know it’s coming. You anticipate it. Moreover, in childbirth, you eventually get to a point where the pain builds and builds and builds to an apex of sorts before coming down — the aptly-named “transition” from contractions to pushing — so in a way, the pain abates a bit. Childbirth pain doesn’t go away, but your focus shifts a bit, and again, you can tell that the end is in sight.

This headache, on the other hand, was completely different.

There was nothing that seemingly set it off, no preexisting condition, and instead, it was a constant rage, a horrible feeling that rendered me extremely uncomfortable to even move my head to look downward and incredibly woozy to stand up. Light and sound didn’t bother me, but closing my eyes seemed to help with the dizziness and fatigue. The pain came out of nowhere, and it was awful and unrelenting. I apologized to my teammates, saying there was no way that I could try to race because I just felt so horrible, and told them to go do their thing while I hung back and tried to ride this out.

After my teammates left to race, I took the seats down in the way-back of my van and lied down in the fetal position, wearing my singlet and warm-ups, wondering what the hell was going on. I vividly remember asking myself shit, am I having a stroke? Is this what an aneurysm feels like? and then quickly telling myself that those thoughts were ludicrous. I convinced myself that people don’t “feel” strokes or aneurysms, and that I wasn’t a candidate for either (based on what I knew about strokes, from my mom’s and Bernadette’s experiences), and that more than likely, this was just a shitty, shitty headache that was probably the beginning of the flu or some nasty infection.

I lied in my car for probably a couple hours, waiting patiently for my teammates to come back, listening to the sounds of the loudspeaker and race announcer, and not really sleeping but instead closing my eyes and waiting for the time to pass. Though I was so incredibly nauseated, I willed myself to keep my shit together in my van simply because I didn’t want to be lying in my own vom for hours (and because I’d surely have to clean it up later. I know my teammates love me and all, but that’s asking a lot). In time, my team returned, and Claire drove my van so I could continue to lie down in the backseat for the two hour drive home. I felt like total and utter ass.

Once I got home, I made my way upstairs, asked C to “do the kids” because I felt so sick, and grabbed a bowl (to vom into) and went to bed. I still felt super nauseated and dizzy, but I thought that maybe some of the headache was due to hunger, since I hadn’t eaten since nearly 5am. I tried to choke down easily-digestible stuff, like crackers and Gatorade, to no avail. I still felt nauseated, and trying to eat food wasn’t doing me any favors. I resorted to my dark, cold, and quiet bedroom, and alternated taking ibuprofen and acetaminophen for the next 24+ hours at this stubborn, nasty headache.

Monday – ER

I checked in with C early Monday morning and asked that he stay home from work — something I rarely ask him to do — and “do the kids” again because I still felt like trash, and I continued to throw ibuprofen and acetaminophen at this headache that just wouldn’t abate. At any given time, I had both OTC drugs coursing in my system and had an icepack on my head — both on the back of my head (where my high ponytail would be, the site of the intense pain) and on my forehead — and at the suggestion of my husband (who habitually has headaches and migraines), tried to prop up my head in such a way as to alleviate any pressure on it or my neck. I had no idea what was going on, and I continued to wait for this shitty flu to finally surface in its entirety; it seemed to be taking its sweet time.

My headache dropped probably from a 10+ to a 9.99 on Monday, after taking a ton of medicine, but by Monday afternoon, it was still raging pretty hard, and I was still feeling abnormally sub-par. I texted my sister, Lauren, a nurse practitioner, and half-jokingly asked her at what point I would inadvertently poison myself between the ibuprofen and acetaminophen. I’ve read enough science/health stuff lately to know that the poison’s in the dose with anything, so I kinda wanted to be sure I was covering my bases, even though I was pretty certain that I wasn’t going to inadvertently kill myself.

Texting my sister was the best thing I did.

That weird-ass question of mine led her, in turn, to ask me a series of questions, and it was when we were on the phone that she basically implored me to go to the ER immediately because it was likely I was having a medical emergency. Lauren knew that I have no history with headaches or migraines, so to have what she was calling “the worst headache of your life,” or in medical jargon, a “thunderclap headache,” was a textbook example of some type of emergency; I think it was in this phone conversation that I first heard “brain bleed” uttered.

I called C, who was out with G trying to get his own medical issues that day situated, asked him to come home ASAP and take me to an ER, and by about 1:45 on Monday (2/5), C, G, and I were in Regional’s ER, which was awash with a sea of humanity. By this point, I had had “the worst headache of my life” for more than 24 hours and had been throwing OTC medicine at it for at least the past 12. (For comparison: imagine setting your kitchen on fire, and then trying to put it out with a strawful of water at a time. It helps … but not really).

Of course, the ER in early February was a veritable zoo. It was packed with people who looked like complete hell, and I couldn’t help but think that if all I came in with was a headache, I’d surely be leaving with the freakin’ flu, which was frustrating. The ER staff gave me Reglan and more acetaminophen to help cut the headache and nausea, gave me a CT scan, and sent me back into the waiting room zoo to await the results.

In the interim, C and G left the ER to go get A from school — apologies for the alphabet soup there — and while I was waiting to hear the CT results, I became irrationally angry. All I wanted to do was lie down, which of course, you can’t do in the ER, and particularly during the height of cold and flu season. I kept pacing the length of the hallway next to the ER — so much so that one of the security guards asked me if something was wrong, if I was ok — and in my anger at the situation — at this stupid headache that wouldn’t go away, at being in an ER during a super sick time of year, of not being able to lie down, of having to wait (and not knowing how long I’d have to wait) — I began to internally lash out. Fuck this ER! Fuck this headache! Fuck waiting for who knows how long! I’m about 2 miles from home; I’ll just go walk home and take more medicine! I was pissed as hell, which is comical because I rarely get angry, but my god, I was enraged. While I was pacing, I was video-chatting with my mom (whom my sister had apprised of the situation), and she reminded me that I was where I needed to be and that I needed to stay there to get checked out, regardless of how long it’d take or how badly I felt.

It was while I was pacing outside the ER, mentally cursing everything that I saw, that the PA who had taken me into the ER initially came back out and was yelling ERIN GARVEY?! ERIN GARVEY?! pretty frantically. Her sense of urgency was unreal, and when I asked her what was up — as we were walking from the triage area back to a room — she said that’d I’d have to sit down first. Hearing those words, coupled with that sense of urgency just seconds earlier when she was yelling out for me, made my stomach drop.

Something was wrong.

With me right beside her, the PA and I approached what had to be nearly 10 different nurses, physicians, PAs, techs, and who knows what else all standing in the ER, and she remarked “this is Erin” before I got ushered quickly into a room. They sized me up, I reciprocated, and I don’t know whose looks were more puzzled. I thought it was so odd that all these people were here — what would they want from me? the hell could be wrong? — and I wasn’t even sitting down on the bed before someone said that my CT revealed that there had been a bleed near my brain and that I immediately needed to get changed into a gown and into more testing, that time was of the essence, that we had to go RIGHT NOW.

This couldn’t be real. This is what my sister warned me about. Not even two hours earlier, two thousand-plus miles away, she told me that I could have a brain bleed, and now, standing in the ER by myself, another 10 practitioners confirmed her suspicion.

I quickly tore off my clothes, joking that once you birth a child, you don’t think twice about changing front of relative medical strangers. As I was wide-eyed and shaking nervously while getting into the standard geometric-design hospital gear, I tried to send a quick text to my husband and to my sister. In the interest of time (and dealing with shaky hands), I instead did what was in hindsight the shittiest thing I could have done and left them both 4-second voice texts along the lines of “I’m in the ER, I’m OK, but they said that the CT scan showed that I have a brain bleed, so I’m going to get more tests… love you bye.” I am such an ass sometimes (sorry!), and everyone in my ER room laughed that I had just left probably the worst voicemail that I could have made. (again, sorry!)

From there, everything happened really, really fast. For as much as I was just bitching to my mom on videochat about how slowly things were moving in the ER, things moved fast when they needed to. After I got into the hospital gear and the staff jammed IVs into me and took whatever vitals they needed, I got wheeled back over to do another CT with contrast. The CTs, both times, were pretty uneventful, and having just had them in the fall for my mystery liver issue, I was familiar enough with the process to not be too fazed by it, especially when they injected the dye intravenously, giving me a weird taste in my mouth and an all-over warming sensation (including the feeling like I had pissed myself). I’m claustrophobic, but honestly, the CTs were so fast that neither one fazed me too much.

After that follow-up CT, I again went back into the ER and just waited, talking to a ton of practitioners in the process, and taking what I now know is the standard NIH Stroke Scale questions, for the first of probably a hundred times. I talked with more providers than I remember, telling them all the same story repeatedly, remarking that I wasn’t having double vision, numbness, tingling, or really any other symptom but neck pain and the searing headache. I felt terrified of course, but everyone was really genial and chatty with me, even joking that see what happens when you run?! Running is the worst! You should be lazy like me! while pointing to their big bellies. It was bizarre, like a weird dream. What the hell was I doing there?

Somewhere in the mix on Monday, I also got an MRI, which was pretty horrible and nerve-wracking. Though I had also had an MRI in the fall for my liver issues, it was a completely different experience (and definitely not emergent then like it was this time around). When my head was MRId, I felt completely claustrophobic, since I was essentially velcroed down (in a medical straight-jacket, more or less) while wearing what felt and looked like a football helmet, with plugs in my ears to mitigate the noise, and in a machine that was completely closed and made me feel like I was being slid into a vault. I was trapped, and if there were an earthquake suddenly, I was totally fucked. (I 1000% thought this as I was strapped down). I completely freaked out, crying and shaking uncontrollably, and it wasn’t until a nurse shot Ativan intravenously in me that I could complete the test. Rationally, I knew how important the MRI was and absolutely wanted to cooperate — because it would be able to give a lot of information about my brain bleed — but emotionally, or mentally anyway, it was basically impossible for me to do in the absence of Ativan.

After those tests, I got wheeled back to my room in the ER, and then to a different one, before C was able to come back over (after taking our kids to a neighbor friend’s house; the entire hospital had a “no kids under 16” policy due to the flu). I was trying to catch-up my sister and C as much as I could, with as much information as I had available to me. C’s mom offered to fly in on Monday night (arriving on Tuesday morning) instead of her scheduled Thursday arrival (for a visit that was already on the books), and my sister was willing to drop everything and get here Tuesday afternoon: both offers that we readily accepted. C and I had no idea what to expect, no idea what would happen for this weird “brain bleed” thing that I apparently had, and while any other time, we figure things out on our own (since our families live thousands of miles away), this time around we took the help without hesitation.

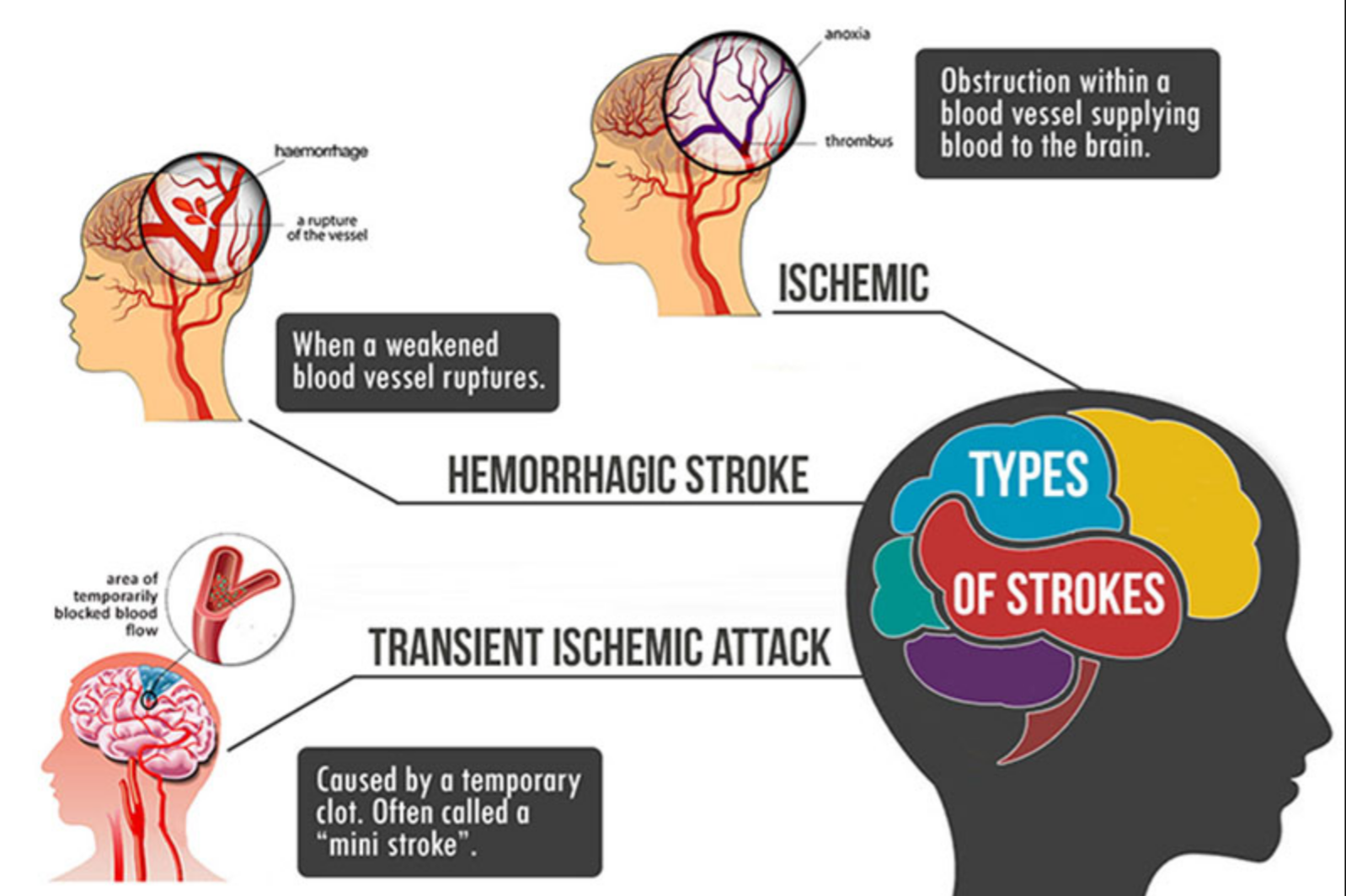

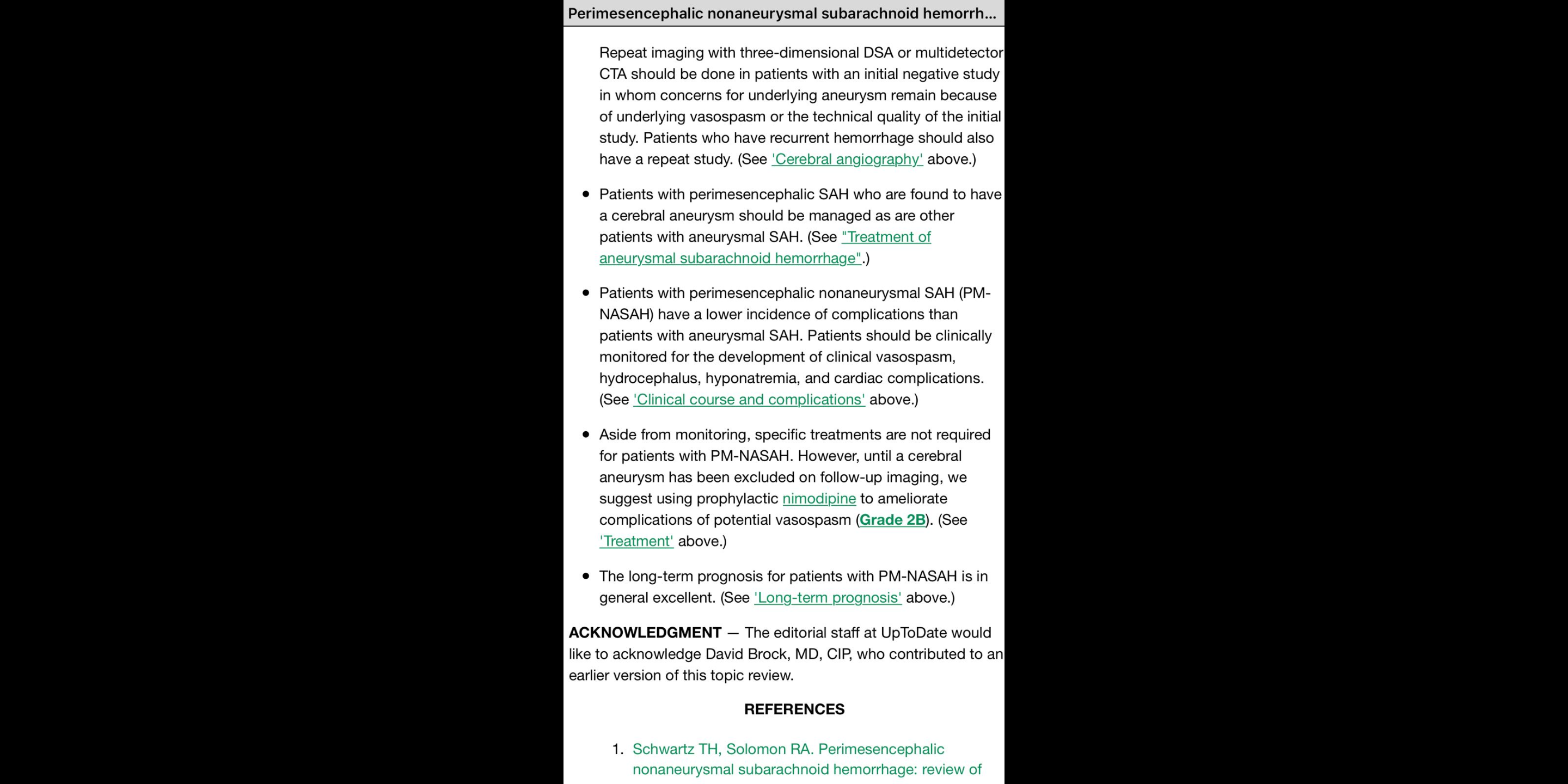

On Monday night, while I was still in the ER, waiting for an ICU bed, my team of Interventional Radiologists came in and explained that they wanted to do an angiogram on Tuesday morning and explained all the inherent risks and benefits. My IR team said they were fairly sure that the bleed — what’s called a subarachnoid hemorrhage, based on the location of the bleed, and which is an example of a brain bleed, which is a type of stroke — wasn’t from a ruptured aneurysm, but the angio would help confirm that.

I had a brain bleed, yes, but as we learned, a brain bleed is a type of hemorrhage, which is a type of stroke. A stroke.

I was 34 years old (34.25, to be precise), super healthy, strong, at a healthy weight, a vegetarian (almost vegan) and marathoner for more than 10 years, a never-smoker, hadn’t drunk alcohol in almost two years, didn’t have high cholesterol or high blood pressure, and had never done any drugs.

Basically, I had zero risk factors, and yet, I had a stroke.

And as of Monday night, no one knew why.

Tuesday-Friday

I spent the rest of the work week in the hospital, almost exclusively in the ICU. I am so profoundly lucky on so many levels with this whole stroke experience, and I count among my luck having family and friends who quickly mobilized and dropped everything to help my family. Friends (whom I’m lucky enough to call neighbors) watched the girls while C was with me in the ER on Monday afternoon/evening, after the medical team diagnosed me with a stroke, and my mother-in-law and sister both booked flights on Monday to arrive early Tuesday morning and Tuesday afternoon, respectively.

We live thousands of miles away from our families, and of course, everyone’s busy with their own lives, jobs, and family obligations, so the fact that my MIL and sister put their lives on hold to help us out was so, so huge. C’s parents were originally planning to come in on Thursday to visit with us for a week, so the timing was actually pretty good, in a weird the universe always makes sense type of way. My MIL helped manage everything that was going on at home with the kids, helping C out where she could, which was enormously helpful. G didn’t seem to mind my absence much, but A was freaked out about it and was telling people at school that I was in the ER because they needed to fix my brain; suffice it to say that it made for some interesting conversations later with the faculty and staff. Having “life as normal,” or as close to normal as possible, at home seemed to help my kids out a lot. For that, I’m tremendously thankful.

My sister arrived to the hospital Tuesday afternoon, once I got moved to the ICU after my angiogram, and for the duration of my hospital stay, she came in first thing in the morning and stayed at my side until visiting hours ended at 9. Having my sister, a medical professional, basically at my bedside was beyond helpful. She knows questions to ask that I simply don’t, and honestly, just having some semblance of “home” in what was a terrifying and jarring experience was huge. I asked her what had to have been hundreds of questions about anything and everything related to this stroke, and she did the same during our many conversations with the nurses, NPs, techs, and physicians. She helped me work through and process a lot of my mental garbage about this stuff, let me cry enough that I could have filled the fucking Pacific, and just simply hung out with me, bullshitting for hours, and watching early 2000s era chick flicks on Netflix while eating copious amounts of Girl Scout cookies. The circumstances that warranted her visit were beyond shitty, but we made the best of it. I will never be able to adequately convey my gratitude to Lauren or my MIL for all that they did for my family and me, but goodness. Again. I’m so lucky.

I hung in ICU from Tuesday, after the angiogram, until about Thursday night, when I got moved to the step-down TCNU unit. During my time in the ICU, my team ran a ton more tests in the hopes of getting some clarification about why I had a stroke. They did an angiogram on Tuesday, additional CTs with and without contrast (I think), a heart echocardiogram, and they even did an ultrasound of my head (which is as weird as it sounds), looking for anything that could have contributed to my stroke or anything that they could have missed, initially, that could lead to another one. Fortunately, everything came back clean. I recalled my IR doctor saying in the ER on Monday night that they were basically going to “back in” to their diagnosis by way of exclusion, intimating that they’d be able to assert that it was because of a blown vein — not an aneurysm, or a blown artery, or something else — that I had the subarachnoid hemorrhage.

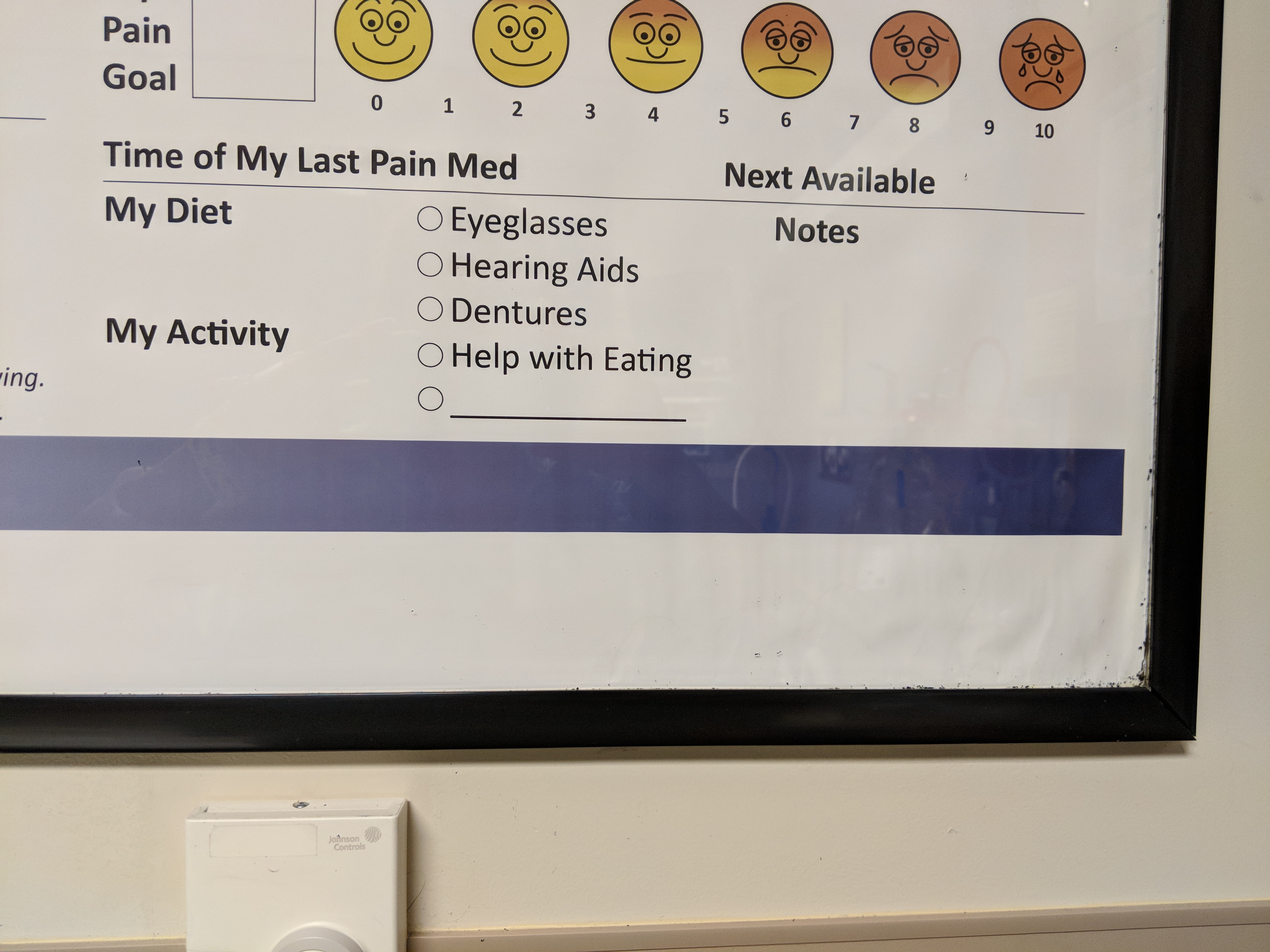

Honestly, when I was in the ICU, and even now, post-discharge, physically, I felt fine. I had a pretty good-sized bruise, about the size of a deck of cards, in my right groin area from the angiogram, but I felt well otherwise. By virtue of the NIH Stroke Scale questionnaire, the medical team repeatedly asked me if I had any pain or tingling on one side versus the other, and I never did. Every sensation I felt on my right side I felt equally on my left. I didn’t have any facial or smile drooping, and my speech wasn’t slurred at all, either. My head still hurt, sure, but that was to be expected; they told me that I’d likely have some sort of residual headache for about a month after the stroke, as the blood from the bleed in my brain metabolized (got absorbed? got broken down? I’m not sure which verb to use here) by my body. The residual headaches have been minor, though, not more than a 4/10 pain at their height, and rectifiable by a couple acetaminophen. (Post-stroke, I’ve been advised to not take ibuprofen because of the increased bleeding risk). The nausea that was so intense on Sunday, the day of my stroke, had basically disappeared by Tuesday morning. I didn’t take much medicine when I was in the ICU, save for my usual thyroid medicine, acetaminophen when needed, and nimodipine, the latter to reduce the risk of cerebral vasospasm and from what I understand, a standard procedure following a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Otherwise, I felt like I was just hanging out and tried to not bother the ICU nurses at all since I was literally the most able-bodied patient there.

Being in the ICU when I physically felt fine was something of a mindfuck, much like this entire experience. I’d have moments and stretches of time when I’d just be enjoying my sister’s or my friends’ company, thinking about whatever it was we were talking about, and then I’d suddenly wonder what am I doing here? Why am I in a hospital, and in an ICU, no less, when I feel (and look) fine? Eventually, reality would hit again, particularly with the onslaught of care and questioning from the medical team, and I’d think oh, yeah.

I’m here because I had a brain bleed.

I’m here because I had a stroke.

I’m 34.

I had a stroke.

I had a stroke.

I could have died.

I had a stroke.

And therein would begin the mindgames, the questioning, the anxiety, the wondering, the wanting to know why did this happen?! And what can I do to prevent this from happening again?! And why didn’t this happen anywhere else in my brain and other associated, shitty-ass existential, mortality-facing soul-searching, replete with what I’m guessing is some type of “survivor’s guilt” and PTSD over the whole experience.

As rational beings, and as adults, we all know we are going to die. It’s a fact and a concept that tons of people struggle with, of course, and one that tons of people fear, naturally, but I’d venture that most of us don’t particularly devote tons of mental bandwidth to it at any given time. Sure, we may experience times in our lives when we feel especially bad and we may think we’re on our deathbeds — but not really — and then the thoughts and fears get buried, tucked away until the next time we feel awful or otherwise get some type of health scare from a doctor’s visit.

Rationally, we — myself included — know that the next time we drive our car, or cross the street, or simply go for a walk outside, we could be struck down dead by anything, at any given time, but the likelihood of that happening is slim to none. Can it happen? Sure. Will it happen? Probably not. It might, absolutely, but there’s a really good chance it won’t. We can’t live our lives in fear, anxious that the super rare what if scenarios will be realized.

The thing that has been most metaphorically crippling with having a stroke at age 34, with no risk factors, and with no warning, has been the loss of control. But are we ever in control of our lives, you may challenge? Well, sure. Yes and no. Certainly we can die or otherwise “lose control” at any given time — see the catastrophizing examples in the above paragraph — but at the same time, I maintain that we do, in fact, have a lot of control in our lives. We have the ability to make informed decisions regarding how we treat our bodies — what we do/don’t consume, how much/little we move, what medicines to/not to take, how much/little we sleep, which relationships to cultivate, and all the other millions of decisions we make over the course of a given day — and common sense (and the medical community alike) would agree that these decisions can profoundly affect our quality (and length of) our lives and of our health.

It was in the quiet moments when I was in the ICU that I’d begin to get in my head about all of this. I’d constantly wonder why this happened to me, when I seemed to do everything “right,” and constantly hearing well-meaning banter from others, along the lines of you this happened to YOU?! You’re the healthiest person I know! You’re a beacon of health! You don’t even drink or eat meat and you run 60 miles a week! didn’t help matters.

I constantly wondered if I had done something wrong, if I had been “penalized,” in some weird, existential or religious sense, for something, anything. Maybe I brought this on myself? Again, rationally, I know that weird shit happens all the time to people — a never-smoker gets lung cancer, an otherwise healthy runner drops dead during a race, stuff along those lines — but accepting that “weird shit happens sometimes” has now become part of my life story, so to speak, has been hard and unsettling.

Needless to say, the mental side to this stroke experience has been rough. Lauren (and others) pointed out to me that I’m thick in the stages of grief, that everything I’m experiencing and feeling is justified and right and not something for which I should apologize, that I instead should just take the feelings as they come. I should feel my feelings, so to speak.

When I run, I often think about my mortality, as I think a lot of runners do. I take time to notice details in my surroundings and revel in their beauty and their presence in the world, stuff like the way the foothills look as the sun is rising or the way the trees smell or even mundane stuff, the minutiae that you wouldn’t see if you weren’t looking for it. I often think how amazing our bodies are, not because I feel I’m at some supermodel-level beauty status or Olympic athlete caliber, but simply because our bodies are so sophisticated and so adaptable to change. When I hit paces or run distances with ease now, stuff that I couldn’t have hit not long ago, I don’t think wow I’m such a badass!; it’s more along the lines of I am so grateful for this body that has grown and birthed two kids and that continues to respond to the challenges I throw at it.

For as much as I think about my own mortality though on the run, and of the fragility of life, and of how, in the big scheme of things, we are on this planet for such a short amount of time (and how we tend to occupy our time with a lot of pretty insignificant stuff), my ruminations about my mortality while I’m running are all on my time. I think them, I convey gratitude to the universe (my body, or whom/whatever) that I’m here and I’m doing stuff and living life in a way that makes me happy and brings me purpose, and I conveniently move on.

Having a stroke, on the other hand, forced me to think about my own mortality in a rather inconvenient, jarring, and scary way, and not on my terms at all. The stroke could have killed me or could have more profoundly altered the rest of my life, had the bleed been bigger, or had it occurred centimeters in any direction elsewhere in my brain than where it did … but it didn’t. And it hadn’t. But that “close call,” that slap in the face, the rationalizing, acknowledging, and accepting that I really truly could have actually died from this if it were worse than it was has been really, really jarring and hard. I remember sitting in the ICU with C one night, and after a chat with the IR doctors, I simply looked at him and said I could have widowed you two days ago. That makes me ill to type.

The stroke has left me more mentally distraught than anything.

By Thursday evening, after getting things sorted out with insurance, even though I was well enough and stable to go home, I got moved to the step-down unit for the night. As a matter of policy, the hospital doesn’t discharge people from the ICU (and with good reason), but if everything went well overnight, I’d be able to go home on Friday. Moving to the TCNU meant that I’d get unplugged from a lot of the monitors and be able to freely walk laps around the floor (which I did, quite gingerly), which was nice, especially after not really moving for five days (which later did a number on my bowels when I got home, ouch). The TCNU staff was as warm and awesome as the ICU staff, and finally, at about 2:15 on Friday, I got discharged (and made it out with my sister in just enough time to go get A from school).

Discharge

I was discharged with specific activity restrictions for four weeks: I wasn’t allowed to run, I couldn’t lift anything heavy, and I definitely couldn’t pick up my kids. The name of the game was to reduce inter-cranial pressure. I didn’t have to take any medicines that I wasn’t taking before I had the stroke (including the nimodipine), and aside from just trying to “take it easy,” so to speak, I could do life as normal.

Of course, immediately post-discharge, every time anything hurt in my head, my mind would revert to shitty, dark places, convincing me that any minor ache was the beginning of another stroke, that my hemorrhage was really just the prelude to one that’d be bigger and worse and assuredly widow-making. When my sinuses hurt, it wasn’t logically because my allergies were raging, it was because a tumor had sprung up since my last scans, and now, my death was now surely eminent … and so on.

The anxiety immediately post-discharge just blew.

On the Monday after my discharge date, I had a follow-up with my new neuro at Stanford (since insurance dictated that I go there, and not to the team I saw in the hospital, to receive care), and he confirmed all of my hospital team’s diagnoses and claims, agreeing that the stroke likely happened because of a weak vein that blew and that we’ll probably never know why it happened, since I don’t have any risk factors. He confirmed stuff that my IR team in the hospital said, that sometimes, weird shit like this happens to everyone and anyone. Both teams relayed stories of it happening to athletes like me (people working out at the gym, someone lifting heavy weights), the FedEx guy who picked up a ton of heavy shit and exerted himself, and even at the opposite end of the spectrum, a person just sitting at his/her cubicle at work, not doing anything strenuous at all. This shit just happens sometimes.

More importantly, having this experience doesn’t predispose me to repeat occurrences in the future, and statistically, random person on the street and I have the same chances of it happening. I think I’ll eventually find solace in this, but for right now, my experiences are still too raw and fresh for me to put my faith in numbers if for no other reason than I had such a low likelihood of it happening to me in the first place, and yet, it did.

My Stanford neuro ordered an MR study about a month after my stroke date to make sure they didn’t miss anything in the first scans, things that could have contributed to the stroke I had or to future ones (like something vascular or some congenital thing) but maintained that he was 99% sure that the follow-up scan would come back clean. He, like my hospital team, anticipate that I’ll make a full recovery, which is fantastic to hear. My sister sent me information about it as well, confirming everything that my doctors all said, and I joked that I need to print out the screenshot she sent me and hang it everywhere in my home so that when I get anxious and fearful, I’ll have it to read.

I started working with a case manager at Stanford to help me manage my care and navigate the bureaucracy, and she has been really helpful so far. She encouraged me, and later helped me, to connect with a counselor because she said that I was likely experiencing some PTSD over the jarring and traumatic nature of this experience, and she also recommended that I consider taking anti-anxiety medicine as needed. I’m more on board with the counseling than with the medicine, simply because I don’t want the side effects that come with benzodiazepines, but we’ll see. My sister returned home the day after I got discharged, C’s parents were here for a about a week thereafter, and then my parents came in to visit about two weeks later for their annual California trip (that I had planned for them last July — again, weird timing), so having lots of people around has been a wonderful distraction.

At this point, I’m just three weeks removed from the stroke and am just a handful of days from my first counseling appointment, and most importantly, my follow-up MR study. Needless to say, February has been both a long and short, weird, strange trip. I am hoping with my everything that I’ll get good news from Saturday’s scan and that beginning sometime next week, I can return to some semblance of life per yoosh with running, lifting, picking up my kids, and just proceeding how I’d proceed, I guess.

I’m still in shock and disbelief, and periodically enraged, that this happened to me, but my sentiments on the matter aren’t going to change that.

Sometimes, shit just happens.

If you’re going to go for a run outside on a clear, cloud-less, blue skies-filled day, you have no reason to think that you may be struck by lightning. Why would you? There aren’t any clouds in the sky; it’s not getting dark and ominous; and fuck, the meteorologist didn’t say a thing about rain. It’s so unlikely to happen that you don’t waste any time hypothesizing about it.

…and yet, it could happen. Unpredictable things happen every single day.

Sometimes, shit just happens.

Realistically, when you consider our bodies’ level of complexity and sophistication, it’s a small wonder that more things don’t go wrong more often than they do.

One day, my brain messed up, not because of anything I did or didn’t do, but because sometimes our bodies make mistakes.

It’s ok.

It sucks, and it is scary, but it’s ok.

I am so lucky that this wasn’t worse, that I got such excellent care, that I have the ability to get the care in the first place, and that so many people have and are continuing to reach out to my family and me to help with anything. My luck isn’t lost on me with any of this.

I think one of the best pieces of racing advice I’ve ever received — and thus give out gratuitously — applies in this situation: control what you can, and let go of what you can’t.

Even though it can be hard to keep my head up with this entire situation, I know how lucky I am. When I get sad and anxious thinking about this stuff, I re-read every message I’ve gotten since this whole debacle unfolded to help buoy my spirits. The love and support from family and friends is palpable to me, and I’m determined to do what I can, to do whatever I can, to get to a place of “normal” for my family and for me. Every day I get just a little further removed from the experience helps bring me a little more taste of “normal,” and for that, I’m really grateful.

Not to cheapen the experience of having a stroke, but again, similar to a race, there will inevitably be shitty stretches of life when things just suck and you feel like your ass got kicked to the curb. Maybe you had some hand in your outcome; maybe you didn’t.

It’s important to acknowledge and remember that just because it happened doesn’t mean that that’s how it’s going to remain.

Just because this nonsense is at the forefront of my mind right now doesn’t mean that that’s where it’s going to stay (and I very much look forward to when I stop thinking about it).

In marathoning, we say to “run the mile that you’re in,” to not necessarily anticipate how you’ll feel in the future or compare to how you felt in the past but to instead, just stay present and focused on the mile or task at hand. Ride it out.

This proverbial “mile” of my life has been rough and unexpected, to say the very least, but I know — or am audaciously hopeful, anyway — that I’ll be ok in time. Remember: the prognosis … is in general excellent. Is in general excellent. Is in general excellent.

My teammate and friend Ashley, who herself survived a life-altering accident a few years ago, reassured me that this experience will make me stronger than I ever thought I was capable of being and that it will give me a perspective on life’s inherent beauty that few people can grasp. I’m finally beginning to understand the magnitude of her words.

Postscript

I so greatly value and appreciate the support and love that so many people have shown my family and me in the past month. Words won’t do any justice, but please know that we are grateful for everything you’ve said or done for us in the past month — the flowers, cards, messages, care packages, delivered dinners, checking-in, everything.

Sincerely: thank you.

Thank you for being excellent.