Peter Sagal’s _The Incomplete Book of Running_: book report

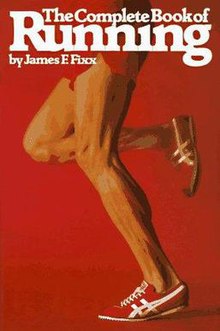

When I began training for my first marathon in 2007, I distinctly remember buying one of those page-a-day daily calendars from a local mall in the north shore suburbs, one that had a red cover on it and featured a lanky and uber-muscular (if not sinewy) male Caucasian’s lower leg, wearing some old school running shoes that were quite reminiscent of what I wore for high school volleyball. It was in that pseudo-training plan calendar that I meticulously and methodically outlined my running for an entire year, as I went from not being able to run a full mile to running my first two marathons within six weeks of each other later that year.

It wouldn’t be til much later in my running “career” that I’d learn that that popular red cover and even more popular leg belonged to Jim Fixx, someone who many would argue single-handedly began the running boom in the late 1970s. It is based on that famous red cover that we can begin talking about NPR commentator and frequent Runner’s World contributing author Peter Sagal’s newest book, The Incomplete Book of Running.

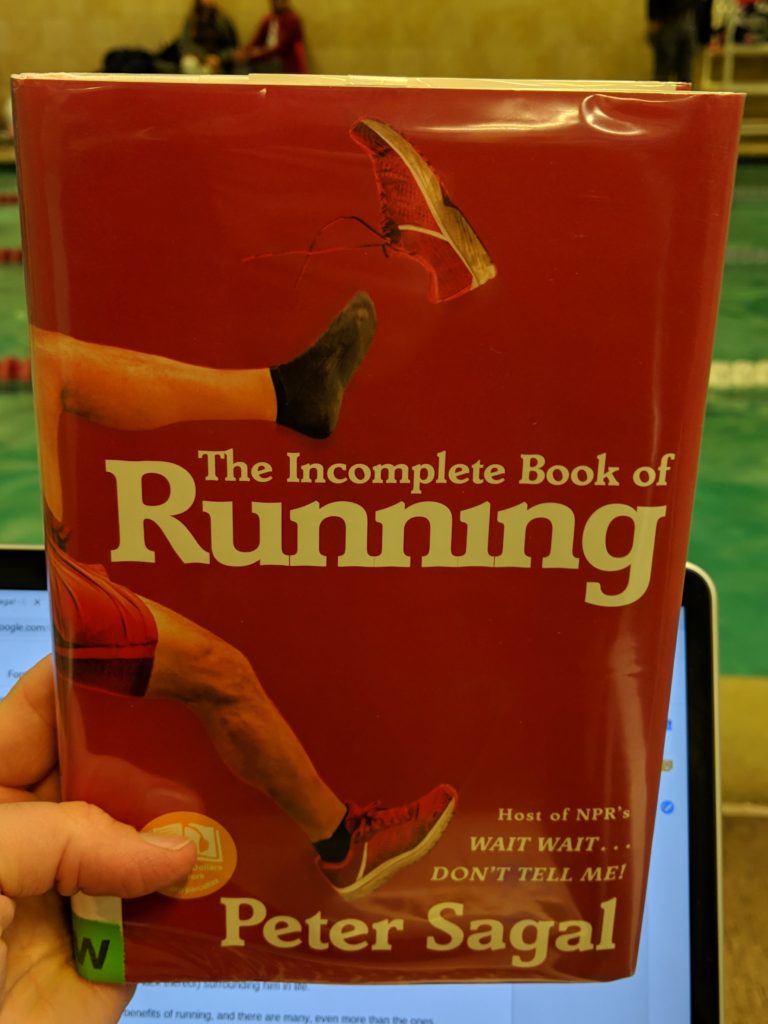

Right off the bat, readers will notice that Sagal’s book looks strikingly similar to Fixx’s: red cover, Caucasian leg, nondescript shoe, although — perhaps predictably — Sagal’s cover quickly brings humor into the conversation, what with the “incomplete” titular reference and his legs being askew and shoes flying off his feet. Sagal is perhaps best known — or what I know him as, anyway — for being the long-running radio personality and host behind NPR’s Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me! comical weekend news radio show, an informative and entertaining bit that aims to bring some amount of levity to what would otherwise surely be a hella depressing job (especially in this political climate).

By virtue of living in Chicago for eleven years, whether warranted or not, I feel like I have a sort of kinship with Sagal: he has lived in a west Chicago suburb for many years, he films Wait Wait at the Chase Auditorium in downtown Chicago (very near my old employer), and tons of friends have seen his show live. (Alas, the one time I purchased tickets for us to see the show, C and I ended up not going because if I recall correctly, we were going to go see the show right after I got back from Kenya, and yours truly contacted something nasty on safari and was too busy bonding with toilets upon re-entry to the US. Fun times).

Probably more pertinent for our purposes here, Sagal runs/ran a lot of the Chicago-area races that I once frequented, making his spotting therein a pretty regular thing; that just adds to that whole aforementioned (un)warranted kinship thing. Like a true runnerd, I once worked up the gall to talk to him while we were both waiting in a high school cafeteria before a half marathon in early March — hi Peter I’m Erin and I’m a fan of your show and your writing and good luck at today’s race oh and at Boston too are you doing Boston yeah me too kthxbye — before quickly realizing that when we’re all wearing a thousand layers of spandex, colorful wicking materials, and comparably copious amounts of anti-chafing cream and lubricating moisturizer to ward off the gnarliest of Chicago-area winds mid-winter, we’re alllllllllll human. And all similarly dorky.

Similarly, there was a time in my life when I was a regular, if not avid, Runner’s World reader and subscriber. Sagal’s column was always one that I looked forward to and one that I always read right away. With little effort, I can tell you about the time when he got crucified for banditing the Chicago Marathon because he wrote about it in RW, for some odd reason, or about how he’s been a sighted runner for visually-impaired racers at the Boston Marathon for the past couple years, or about that one time he ran in his underwear for a Cupid’s Run somewhere. I can vaguely recall him writing about his training for the Philadelphia Marathon, a big PR day for him, and about the work he took to get that sub-3:10 effort. He’s a good writer, equally informative, entertaining, and inspiring, and I loved reading his stuff.

Given everything that I already knew about Sagal’s running career over the past few years, I wasn’t sure what I was going to get out of his book. It doesn’t read like a linear autobiography, something that recounts his earliest interactions with the sport and ends it in the present day. Instead, each chapter offers a moment in time in his running tenure — including, but not limited to, how and why he began running, the two times when he served as a sighted runner in the Boston Marathon (and how he very, very narrowly missed being in the finish chute when the bombs detonated), how his running (via his radio show) has allowed him to explore the US in fairly profound ways, and his PR training and race execution at Philly. He punctuates each vignette, if you want to call it that, with general ruminations about the sport of running, overall, and marathoning, specifically, as he more or less implores each of us to get outside our heads and just keep the thing, the thing, and just go do the thing FFS.

I’ve always felt that running is an incredible equalizing agent, and Sagal’s ruminations in this regard left me shaking my head in agreement so often, and so vigorously, that I’m surprised that it didn’t leave me with neck strain. If I weren’t borrowing this book from a library, I’d be highlighting the shit of out of lot of his commentary. Non-runners tend to think that runners one day just magically woke up, decided I’M GOING TO BE A RUNNER TODAY!, and simply sprinted out the door at 5:50 pace for 20 miles. Of course — maybe save for the professionals in the room — that’s simply not the case for the overwhelming majority of the runner plebeian society. For most of us, this stuff is super hard and damn near impossible at first.

Very few of us talk about how hard running is and how hard it is to get started — how much it utterly sucks at times, how hard it is to not compare ourselves to our peers or to our “glory days,” assuming we had ever had any in the first place, and how hard it is sometimes to just get our butts out the door in the cold, rain, wind, snow, dark, sun, heat, whatever to do this thing that we know is good for us and that we actually enjoy when it’s all said and done (the “said and done” being the operative parts of that sentence). Sagal doesn’t shy from talking about all of these rather undesirable tenets of running and doesn’t balk from essentially saying yes, it really sucks sometimes, and hey you may even shit yourself a few times, but just a few steps can take you a long ways over the course of your lifetime. His story is a testament to this, and you may find your narrative is similar to his. I know I did.

Even though I found some of Sagal’s staccato comedic fill-ins to be slightly annoying at times — I love me some dad jokes and clever bantering as much as the next person, but still — and some of his run-related ruminating a bit sanctimonious — I don’t enjoy running on treadmills, but I’m not going to imply that runners who do are any “less” a runner — I think the biggest takeaway from Sagal’s writing is how embedded he has made his running to his mental health, how important an element his daily miles have become in making him the healthiest version of himself, both physically and mentally. It’s an oversimplification to say that his book is about himself, a more or less lifelong runner, who found himself at mid-life with a crisis and used his running to get through it all. It is about that, yes, but there’s so much more to the story.

It is clear from nearly page one that running plays a huge role in his mental wellness and that it was one of the few constants in his life through some pretty shitty times. How many of us can relate to that? That he, as a public figure, had the courage to talk about his mental health struggles is commendable and admirable, and that he talks about how important his running has become for multiple dimensions of his health I think can inspire all of us to talk about the same with our own health providers with similar frankness and candor. There’s so much out there now about running being therapeutic — the subject of my current read — and Sagal’s story is but one example.

The general, non-running public tends to think that we run simply for the cardiovascular benefits it imparts; that running can do a number for your mental health is seemingly the best-kept secret there is but one that we need not keep to ourselves any longer. It’s a secret worth sharing because it’ll do the world a world of good, and the world sure needs a lot of good right now. Sagal went through some pretty crappy mid-life stuff, and in his words, running was one of the few things over which he felt he had any control or agency. Again: how many of us can relate to that?

Prior to reading this book, I knew nothing about Sagal’s apparently quite difficult and quite drawn-out divorce following a 19-year marriage, nor did I know anything about how said divorce seemingly alienated or estranged him, at least temporarily, from his three teenaged daughters, as they all were trying to equilibrate following and during this major life change. He doesn’t mince words as he talks about the grieving process he experienced during what sounded like many tumultuous years of essentially starting over, not knowing if he’d ever find himself in a caretaking capacity again as he had been as a husband and father, and coming to terms with the futility of it all, an existential crisis that was years in the making and that simply catastrophized with the deterioration of his marriage. This stuff isn’t for the faint of heart.

Having friends going through these motions right now made Sagal’s writing hit a stronger, more personal chord, and I felt completely gutted for him. I couldn’t read his words without thinking of my friends, and at times, it took my breath away. He doesn’t devote an entire chapter to his divorce or starting over or anything like that, however; instead, he usually brings it up as a quick reorientation, a subtle reminder of the present-day that was a backdrop to all his running experiences in his life. In fact, for example, it was due to a coalescing of these events that led him to sighting at Boston the first time, something that surprised me simply because when it was actually happening, I don’t recall ever reading about it before. Though he was in the thick of his divorce at that time, the sighting experiences profoundly affected him and arguably played a bigger-than-anticipated role in his life at that time and since.

The same thing goes for when he was a participant and a major fundraiser in a Cupid’s Run during Valentine’s Day; I can recall reading a RW column about it and just thinking oh that’s nice, Peter Sagal is running somewhere in his underwear for charity. How nice of him.

It’s a good reminder that when we’re on the starting line at any race, our fellow racers (and perhaps us, too) are carrying with them some pretty powerful stories and burdens. We’re all there to run hard and fast, yes, but for many, it’s about something much greater.

We will speed up and slow down, perhaps run farther or shorter distances than ever before as we age, but the process — the bread and butter of putting one foot in front of the other, repeatedly — that doesn’t change.

In a world where change is the only constant, there is something special — holy, even — about the process of running and the gamut of emotions it engenders remaining the same, no matter the noise and chaos that surrounds us. Csikszentmihalyi is onto something.

We who run intuitively know this to be true, and the science — particularly related to mental health and exercise, and specifically to running — is beginning to catch-up.

If you’re looking for a training book about how to run your best race, Sagal’s book isn’t it.

If you’re looking for a definitive autobiography or memoir about Sagal and his professional life, this one isn’t it, either.

If you’re looking for a brutally candid account of the transformative power of the oldest sport on the planet, the one that we all come out innately knowing how to do, the one that is arguably one of the most cathartic motions we can do with our bodies, Sagal’s Incomplete Book of Running is it.

His love for the sport couldn’t be more evident, but his evangelism doesn’t come without a healthy amount of admission that sometimes — ahem, often — this sport is hella hard. His book is incomplete because his running story is incomplete, as is the case for all of us who run. We’ll never know where our miles will take us unless and until we go out and just simply run them.

Though Sagal may think that his fastest days are behind him, and that his drive to surpass his fastest times is long-gone, he’s a lifer in this sport. It’s a status to which all of us who love this sport should aspire. Regardless of his mile splits or his weekly volume, so long as he continues to run for the rest of his life, he will continue to reap the incalculable benefits that putting one foot in front of the other, hundreds if not thousands of times yields, no matter the shitstorm (or lack thereof) surrounding him in life.

Running is a gift that can keep on giving, no matter, and Sagal’s account is a testament to that.

And maybe, too, a habit of hope. Running sometimes sucks, but every run ends, and tomorrow is a new opportunity to take a first step” (180).