COVID, week 54 + Alexi Pappas’s Bravey – book review

I mentioned last week that a COVID-induced change that I hope sticks around is the relatively new openness, or comfort, that more people seem to have when it comes to talking about mental illness.

As we all can attest, the pandemic has upended life, so profoundly, in so many different ways, for so many, that more people are citing mental health maladies in the past year, than perhaps ever before. (Admittedly though, let me own that I don’t have the actual stats to back that up, but I think it’s a logical conclusion, based on what we do know. The pandemic also forced many providers into telehealth settings, which is another COVID-induced change that I hope sticks around. More treatment options = more opportunities for people to seek care. That’s a win in my book).

Anyway. With mental health becoming a significant conversation piece over the past year, it has been illuminating to see additional coverage of mental health-related topics. I think it’s especially interesting coming from athletes (and runners, in particular), people whom you may, at first glance, assume have it all, have their shit together, what have you. Many people unduly think that one’s prestige or accolades may protect him/her from the grips of mental health despair, but cursory observations show that that’s not always the case.

Enter: Alexi Pappas and the New York Times, early December, 2020.

A lot of runners may know her for her time at the University of Oregon, her impressive track speed, perhaps her debut at the marathon distance in Chicago a few years back, and/or that she set a Greek 10k national record during the ‘16 Olympics in Rio; she’s a decorated athlete, for sure. (And of course, this is to say nothing of her creative pursuits).

Before the New York Times op-doc she and Lindsay Crouse released in December — ahead of her book’s publication in January — many of us, myself included, probably didn’t connect her and mental health in the same breath.

If you haven’t yet watched or read the NYT piece, do that first; I’ll be here.

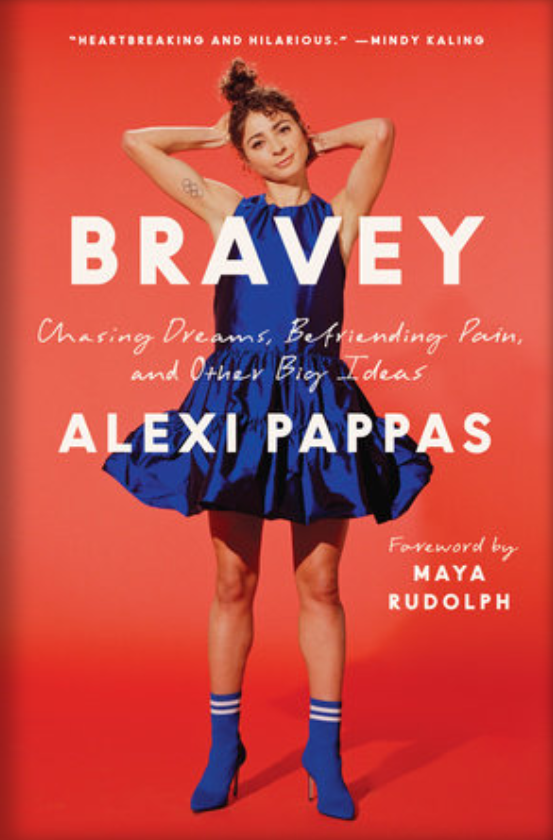

It’s pretty powerful stuff and an excellent segue into Alexi’s newly-released memoir-in-essay, Bravey.

I recently procured a library copy of Bravey and tore through it in a few days’ time, between pockets of distance learning. Admittedly, I knew very little about Alexi Pappas’s life, beyond what I just mentioned above; I had little-to-no knowledge about the filmmaker side of her life, her marriage, her upbringing, nothing. She’s even from the Bay Area (Alameda), and I had no clue; I feel like everyone local should know that!

I knew from watching the aforementioned NYT op-doc in December that she suffered from depression after the ‘16 Olympics, but I was gleefully ignorant about its severity or depth — or her family history — until the earliest pages of her memoir-in-essay.

Powerful is what I keep returning to, as I try to describe Alexi’s life story, but I think that sells it short. There’s a lot going on in its three-hundred-plus pages.

It’s a woman’s life story, yes, but it’s more than that.

It’s ruminations from an Olympic professional runner, yes, but it’s more than that.

It’s the life story from a mental health consumer — whose own life and upbringing was very deeply affected by her mother’s mental health challenges — yes, but it’s more than that.

I don’t really know how best to describe it, to be honest.

When I finished reading it, I knew I needed to write about it, but where to begin?

Or how exactly to convince you that you need to read it? I don’t know, but it’s urgent that you add it to your queue.

Alexi punctuates each chapter in Bravey with lines of her own poetry — she turned down competitive, rare MFA poetry scholarships to pursue a fifth year at Oregon to eventually launch her pro career — and as readers become more familiar with her life, the short verses read less like the whimsical “gotchas” they may seem at first glance and more melancholic, given her story.

In the earliest pages of her memoir, Alexi shares with readers that she lost her mother when she was four years old to suicide and that for years, she, Alexi, didn’t know. Her mother smoked cigarettes; as a young girl, Alexi knew that cigarettes could kill you; her logical conclusion, as a four year-old, then was that her mother died because she smoked cigarettes.

It is absolutely gutting to read.

Alexi describes some of the numerous times when her mother sought in-patient treatment for her mental illness — and her periodic, harrowing reprieves at home, and what Alexi remembers witnessing — and her descriptions give readers the type of unfiltered, heart-breaking, and honest impressions of the gravity of her mother’s precarious health that only a small child, witnessing it all go down, can provide.

It is profoundly tragic and uncomfortable to read but obviously critically important.

Each essay in her book could stand on its own, independent from the rest of the chapters, but I think as a writer, Alexi brilliantly wove her story together. Not every essay is about her mother’s death, per se, but clearly the loss of her mother permeates her life in obvious and not-so-obvious ways.

It’s the same with her running career and her filmmaking, writing, and creative career; it’s disingenuous to think that each lives on its own island, liberated from the other, but she doesn’t necessarily devote every single piece to all of the aforementioned.

She makes all of her decisions — about her Olympic aspirations, her professional running career, her creative pursuits and unconventional career with her husband — informed by all of it, even when, at times, it may appear to be competing interests.

In many ways, readers could describe much of her memoir-in-essays as a love and appreciation letter to her father, who single-handedly raised her and her older brother, void of most female mentors, for much of her life. It is from the dearth of female role models that her father felt compelled to enroll her in both Girl Scouts and sports from a young age, and the latter — certainly influenced by her father’s athleticism when she was growing up — arguably helped get her wheels in motion to aspire to Olympic greatness, even as a young child.

I absolutely love and gravitate toward professional athletes’ memoirs (and runners’ in particular) because I like to learn about how everything played out, getting them to where they ultimately end up, because in some small way, us plebs can usually relate.

Alexi’s story is so memorable because, yes, it’s about the aforedescribed and her obvious innate and earned talent, but it’s also a front-row seat to her ongoing self-examination for which a lot of the time, she has no clear-cut, direct answers.

Her acute awareness that she lacked female role models in her life for so long — and her attempts to fill that void (a la Girl Scouts, initially) — permeate her story and definitely inform her experience, even down to the scrutiny she places on her social media presence. She knows that there is always someone watching — perhaps a little girl like she once was, someone looking for a female role model to fill a void — and it’s fascinating to see this thread wind through her lived experience.

When Alexi, herself, becomes severely ill after the Rio Olympics with her own mental health maladies, in time, she — and us readers, along for the ride — realize that the connection she shares with her mother is much less abstract than she once thought. Just as it is elsewhere in the book, when she explores her mother’s illness, the vulnerability through which Alexi describes her own illness — and how it affected her life, career, relationships, her Nike contract, all of it — is deeply uncomfortable and may leave you feeling like a bit of a voyeur, like you’re passing by a terrible car accident but can’t not look.

That’s the point, I’d argue. The less we talk about this stuff — or rather, the more we continue not talking about it — the more it lives and breeds in darkness and isolation, and the more it’s fueled by unnecessary shame, embarrassment, and stigma.

…which gets us to the point, of what it means to be brave, or to be in Alexi’s crew of braveys. She rightfully acknowledges that systemic issues like racism preclude many people from being able to fully realize that which they seek, regardless of how brave they may be.

For her, being brave — becoming a bravey — has meant seeking out the opportunities for growth, even if it means that said growth is accompanied by a whole bunch of discomfort. Mood follows action.

“not your first

not your last

enjoy your now

now will go fast”

(112)

“run like a bravey

sleep like a baby

dream like a crazy

replace can’t with maybe”

(6)

This “mini-movement” of braveys that she created is

“inward facing, a choice you make about your relationship with yourself. We all have dreams that we’re chasing, however big or small, and we can all decide to be brave enough to give ourselves a chance. I think that’s why the term resonated with so many people: Anyone can be a Bravey, and the permutations of what that means are infinite. It’s a switch you flip in your mind.”

(7)

Re-reading these excerpts, the foundation of Alexi’s story, certainly lands a little bit differently once you know what it took to get her there, to that realization. It is shitty that she has had to endure so much to get to that place, but we are lucky that she has so graciously tried to share her painful, lived experiences with us.

I, for sure, am most grateful for Alexi Pappas’s bravery.

Be safe and well, friends. xo